What We Get Wrong About Customer Experience

This week I spoke at Conversion Boost in Copenhagen, a CRO conference that gathers some of the smartest people in experimentation, digital analytics, and UX.

As always, the energy was high, the talks were great, and the case studies were full of uplift charts and confetti-worthy KPIs. But as the day went on, a familiar tension surfaced.

We were all talking about “customer experience,” yet everything we discussed was anchored in the interface: page speed, form fields, copy changes, mobile navs, checkout tweaks. In other words: the final 5% of the journey.

I get it though, I’ve worked in optimization for over a decade. I know the constraints. I know what stakeholders care about, what gets approved, and what gets deprioritized.

But I’ve also seen how this hyperfocus on the visible layer of experience has gradually turned CRO into a high-velocity but low-impact discipline.

A/B tests get shipped, wins get logged, and yet somehow… customer experience remains this unsolved puzzle that keeps resetting every quarter.

So here’s the uncomfortable question: If we only evaluate what’s easy to measure, are we really optimizing experience, or just our interfaces?

That question has been bothering me for over two years. And in this week’s newsletter, I want to start introducing some of the thinking I’ve been developing and some ideas that will eventually become part of a larger paper and a public framework I plan to release later this year. Not a new tool or anything, but a new mindset.

My goal is to make it freely available to practitioners, analysts, and anyone tired of pretending that surface-level metrics are enough.

Table of Contents

Legacy methods in a new context

The modern optimization stack is built on a set of legacy assumptions: that people arrive on websites with clean intent, that friction is mostly interface-related, and that experiences are linear enough to be dissected by funnels, heatmaps, and heuristic evaluations.

These methods aren’t necessary all useless, but they are insufficient.

Heuristic evaluations, for example, were designed to identify usability flaws, not contextual disconnects. Funnel analysis tells you where people drop off, but not why they came, what they expected, or what shaped their perception before landing on your site. And “best practices” are often just survivorship bias dressed up as strategy, what worked in one context, abstracted into something safe enough to scale.

The reality is that these tools and methods were built for a web that no longer exists.

Interfaces used to be the experience. Now, they’re just endpoints.

What actually shapes “experience” today?

In most organizations, “customer experience” is still defined through what happens on the website or app. Performance is measured by what users click, how far they scroll, or whether they complete a flow. But this approach assumes people arrive clean, without bias, emotion, or context.

That’s not how modern experience works.

Experience today is shaped by interpretation. And interpretation is increasingly driven by prior exposure, social framing, and platform-embedded cues that happen before someone ever lands in your owned environment.

Classic behavioral research, like the work of Kahneman and Tversky on framing effects (which everyone likes to quote lol), laid the foundation for sure: people don’t evaluate content or choices in a vacuum, they interpret them through prior mental models. But today those models aren’t only shaped by memory or personal bias.

They’re shaped by the algorithmic surfacing of content, the narratives people absorb across decentralized platforms, and the rapid-fire emotional associations triggered by design, community, and tone.

In other words: Experience starts before interaction.

Today’s customer arrives with a backstory you didn’t author.

A backstory developed through TikTok, Reddit, YouTube, Slack communities, WhatsApp groups, product review aggregators, and their colleague’s casual one-liner (“Don’t use that tool, we tried it. It’s shit.”)

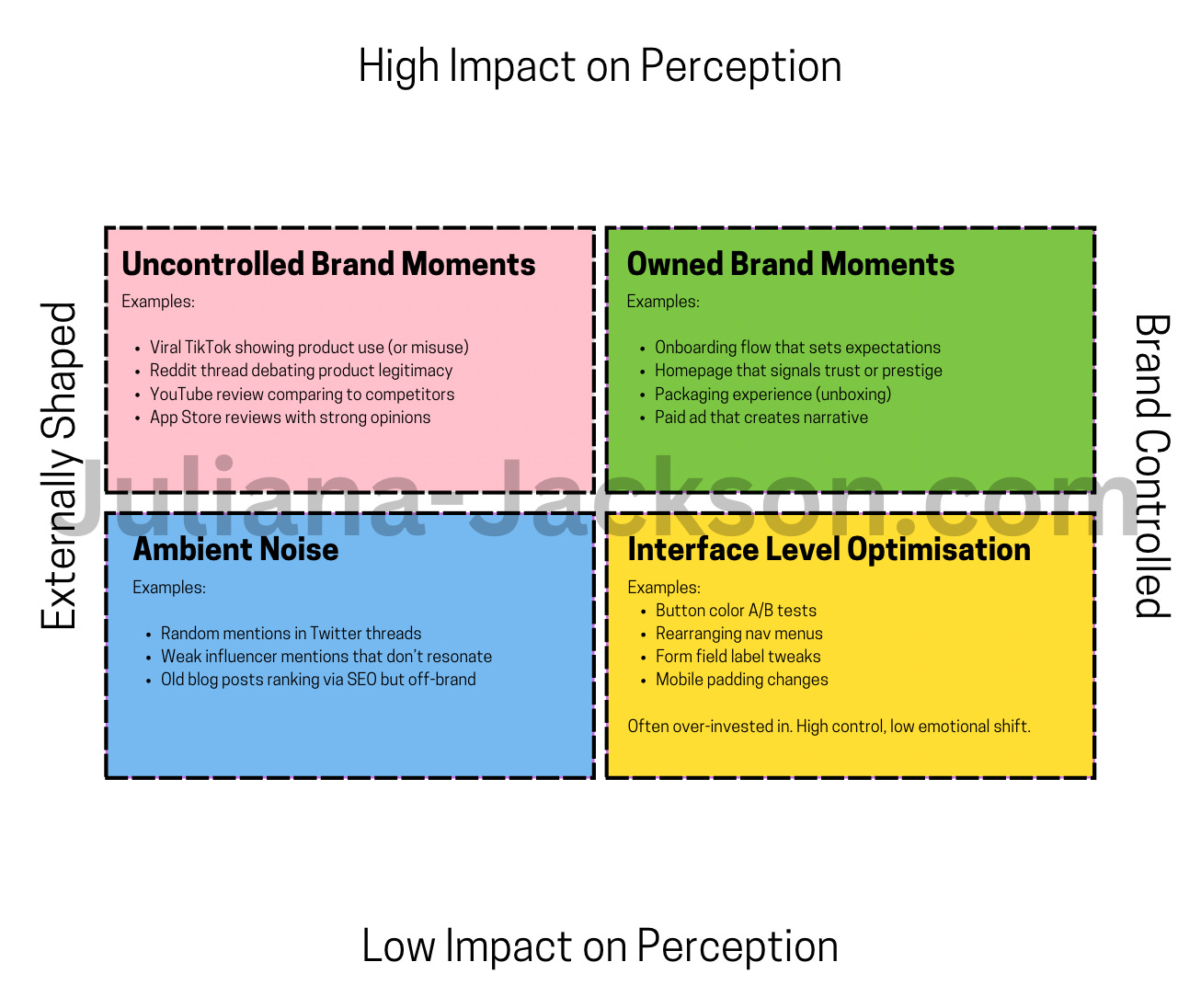

These are Brand Moments. Not touchpoints, but the emotional and cognitive preconditions that determine how your interface, product, services are perceived.

A Brand Moment is any contextual input that shapes perception of a brand, regardless of whether the brand owns it, initiated it, or is even aware of it.

These moments frame whether your landing page reads as credible or confusing. Whether your onboarding feels intuitive or condescending or whether your offer seems generous or desperate.

They’re upstream from your interface, but downstream from the user’s judgment.

And they rarely get factored into how we build or evaluate experience.

Operationalizing Brand Moments: How CRO Can Surface and Use Them

Recognizing that Brand Moments shape experience is just the first step. The harder, and more important task is figuring out how to operationalize them.

How can CRO teams, whose tools and methods are traditionally interface-bound, detect and respond to moments that happen off-platform, pre-session, or emotionally downstream?

The key is to stop treating perception as an abstract force and start treating it as data: imperfect, distributed, and qualitative, yes, but absolutely accessible.

Brand Moments aren’t intangible. They just live in places we’ve historically ignored: comment sections, search results, customer support logs, YouTube videos, unstructured survey responses.

When someone says, “I thought this would be easier,” or “This wasn’t what I expected,” that’s not a necessarily a usability critique it’s a narrative signal. It tells you what story they were carrying when they arrived.

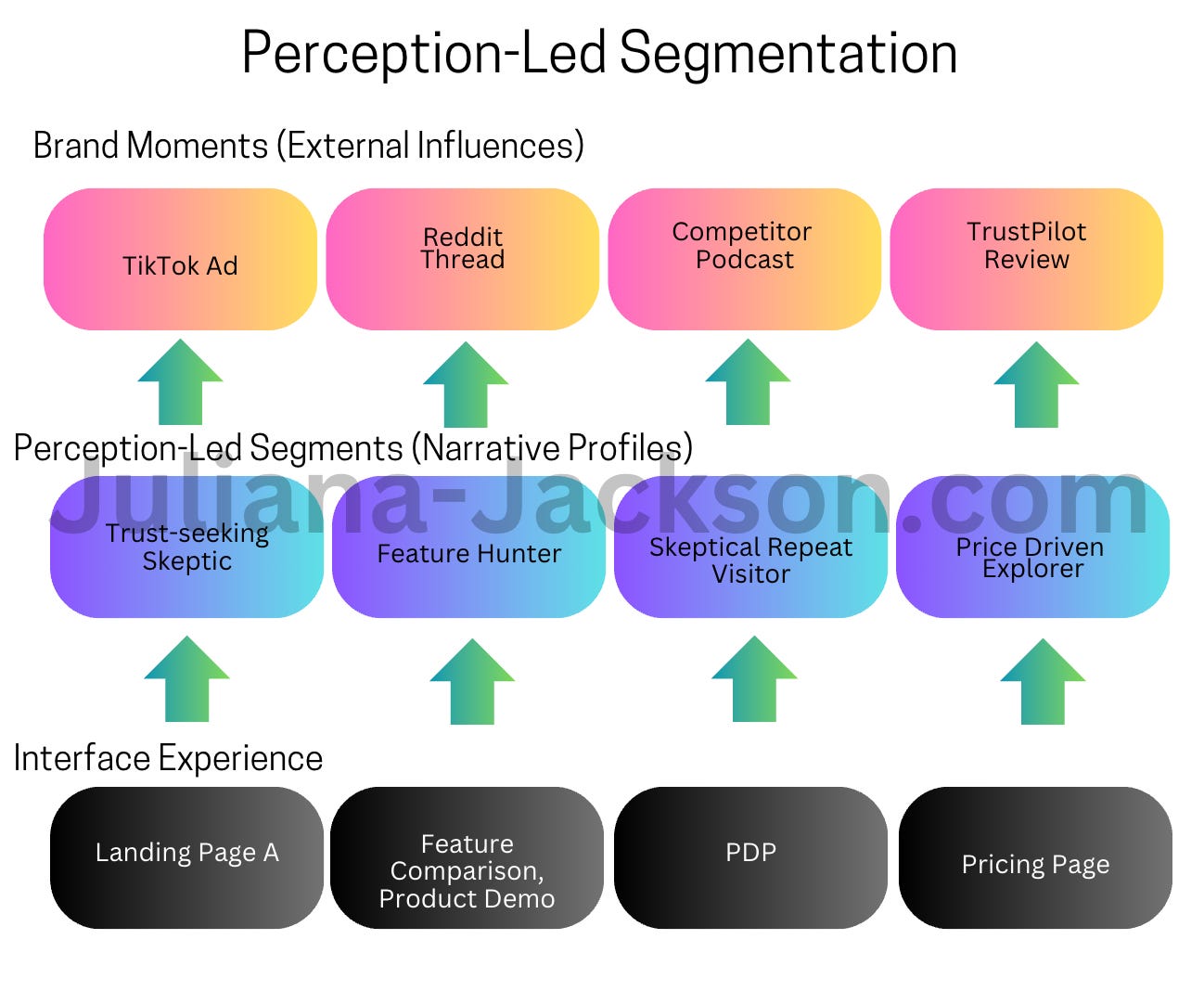

To use Brand Moments strategically, CRO needs to shift from interface-led analysis to what I name perception-led segmentation: grouping users not by where they dropped off, but by what primed their expectations in the first place.

A TikTok viewer who swiped up on an ad isn’t entering with the same framing as someone who clicked a product comparison link from Reddit. Their intent signatures are fundamentally different, even if they arrive on the same landing page.

So how do we start surfacing Brand Moments?

First, we need to expand our signal set beyond analytics events.

Brand Moments hide in:

- Search queries: “Is [brand] worth it?”, “[brand] vs [competitor]”, “[brand] data breach”

- Social listening: Reddit threads, TikTok comment sections, Instagram DMs, YouTube “does this actually work?” videos (there are so many social listening tools that do this like Brandwatch, Sprinklr, etc)

- Support interactions: tags and transcripts that reveal repeated disconnects between what was promised and what was delivered

- App store reviews: raw, unfiltered perception, often loaded with unmet expectations

- Open-text NPS or CSAT comments: where people tell you what actually matters to them, unprompted

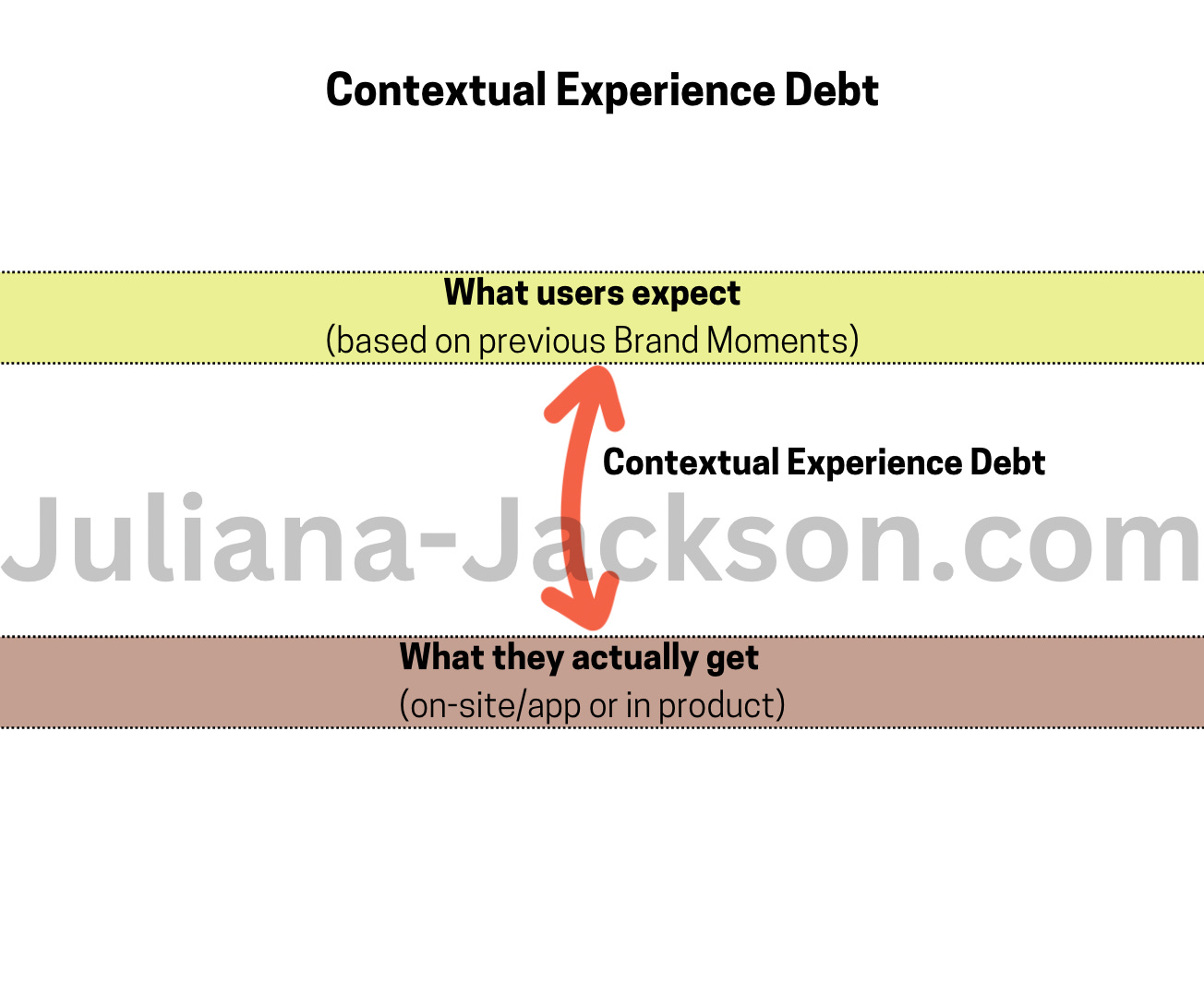

These sources give us narrative context. When analyzed collectively, they show what people think they’re about to experience and where the breakdowns happen. This is what I call the Contextual Experience Debt.

Next, we categorize these Brand Moments not by channel, but by expectation type. This creates a framework for interpreting how moments affect conversion behavior:

- Trust expectations — “Can I rely on this brand?”

- Value expectations — “Is this worth the price / time / switch?”

- Identity expectations — “Is this for people like me?”

- Ease expectations — “Will this be smooth, or will it frustrate me?”

- Outcome expectations — “Will I get what I’m here for?”

Once you have these clusters, you can build hypotheses that map back to Brand Moments. For example:

- If you notice TikTok comments repeatedly asking whether your product is “legit” or “another dropship scam,” that’s not a content issue it’s a trust perception gap. Your test plan shouldn’t start with layout changes. It should start with signaling legitimacy: visual cues, policy transparency, and UX proof points.

- If product reviews show users expected a feature you don’t offer, your challenge isn’t in the PDP copy. It’s upstream, the mismatch between what your acquisition narrative promised and what the product delivers.

Brand Moment mapping also improves segmentation.

Instead of relying solely on traffic source or device type, segment by intent formation path.

Users who came via a viral TikTok are operating with a different mental model than those who searched “[brand] vs [competitor]” on Google. That difference should shape how you design the experience, not just the headline, but the tone, information density, even what default state they see first.

This doesn’t mean every test needs to respond to every narrative.

But it does mean your test strategy should reflect the perception environment your brand operates in. Right now, most A/B tests assume users are seeing your interface for the first time. That assumption is wrong. In reality, they’re arriving mid-narrative with beliefs, doubts, and hopes shaped by a thousand off-domain signals.

Brand Moments give you access to that narrative layer. And once you start working from it, experimentation becomes less about tweaking interfaces and more about repairing or amplifying the stories people already believe.

Perception is the missing variable in experience optimization

I’ve been fixated on Brand Moments and perception dynamics ever since I started working with language models and NLP.

Once you start unpacking how people use language to express assumptions, expectations, and emotional reactions to brands, it becomes very hard to see “conversion” as a single point in a flow.

You realize that what looks like a decision is often just the end of a narrative arc that started long before anyone clicked anything.

That shift in lens is what led me to develop the frameworks introduced in this piece:

- Brand Moments — the emotionally loaded, often uncontrolled interactions that shape perception upstream of any owned interface.

- Contextual Experience Debt — the compounding gap between what users expect (based on prior exposure) and what your interface or product actually delivers.

- Perception-Led Segmentation — grouping users based on how intent was shaped, not just where they came from or what they clicked.

These ideas didn’t come out of nowhere, they emerged from the disconnect I kept seeing between what teams thought they were optimizing, and what actually shaped user behavior. Especially in experimentation programs that were running test after test, but never really moving the needle.

So no, this isn’t an attempt to coin new terminology for the sake of it. It’s a proposal to rethink how we define and measure experience.

Because as it stands today, most CRO work is built on incomplete models of behavior.

I talk about this more on my newsletter, go ahead and subscribe to learn more.